New Zealand Whales

Characteristics

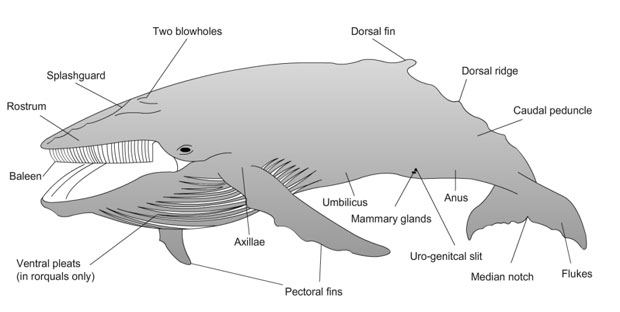

All whales are long and streamlined. They lack external hind limbs but have powerful tails that provide propulsion. Often they lift their tails above the surface before diving – an action known as fluking.

Whales also have a layer of fat under the skin known as blubber, which can be up to 50 centimetres thick. Blubber stores energy and insulates the whale from the cold in deep water. It is thought that whales live for 30 to 80 years.

Baleen whales

There are two types of whale: baleen and toothed.

Baleen whales have long bristle-fringed plates, known as baleen, which are made of keratin (a protein also found in human hair and fingernails) and fixed to the roof of the mouth. These sieve the minute crustaceans, such as krill, that they feed on. Baleen whales have two blowholes. And unlike some other whales, they do not use echolocation (emitting sounds to locate solid objects).

Baleen whales include the largest animals ever known. Greatest of all is the blue whale; the heaviest ever recorded was a female of 190 tonnes. Baleen whales migrate through New Zealand waters on their way south to feed on krill, which are abundant in the Southern Ocean. Of the world’s 13 species of baleen whales, eight are known in New Zealand, but only two, the southern right whale and Bryde’s whale, breed in New Zealand waters.

Toothed whales

Toothed whales have teeth, rather than baleen, and a single blowhole. They find their prey through echolocation, emitting a series of clicks that travel through the water until they meet an object and are reflected back. By using a range of frequencies the whale can make a detailed examination of the object. Some scientists have suggested that the clicks may stun the prey. Toothed whales include sperm whales, which are relatively common around New Zealand, and the much rarer beaked whales, which have a small head with a beak and a bulging forehead.

Blue Whale

The blue whale is the largest animal ever to live. On average, adults weigh between 100 and 120 tonnes, and males are 23 metres long, while females are 24 metres. The whale’s heart weighs 2 tonnes and pumps about 270 litres with each beat. A child could fit inside the aorta (the blood vessel leaving the heart), and the main arteries are the diameter of sewer pipes. Even when the blue whale is under the greatest strain, its heart rate is no more than 20 beats a minute – compared with a human rate of 60–80.

Diet

On a diet of over 200 litres of milk a day, a whale calf puts on 90 kilograms daily, and by weaning time eight months after birth, it can weigh more than 20 tonnes. An adult was once found to have 1 tonne of food, mainly krill, in its stomach.

Appearance

Blue whales are a mottled blue-grey and acquire a yellowish sheen from algae on their skins, explaining their common name ‘sulfur-bottoms’. Their tiny dorsal fin is set far back on the body. They have the loudest voice underwater of all animals, and their low frequency sounds travel hundreds of kilometres.

Population and migration

Blue whales were plentiful until the end of the 19th century because their speed (30 kilometres per hour) gave them the edge on non-motorised chaser boats. Hunted relentlessly in the 20th century, their numbers have plummeted. There are estimated to be fewer than 2,000 in the southern hemisphere. On their migration between the summer feeding grounds in the Antarctic and the equatorial waters where they spend the winter, blue whales used to swim through Cook Strait, and during the 19th and 20th centuries Tory Channel whalers would sometimes kill one. Blue whales still migrate past the New Zealand coasts, but are rarely seen close to shore.

Fin Whale

Fin whales, named for their prominent dorsal fin, are rare in New Zealand waters. The second longest of the whales at an average 20 metres, the fin whale has an asymmetrical colour scheme as its right jaw, but not its left, is white. It is believed that they live up to 80 years.

Sounds

The fin whale produces the lowest frequency sound in nature – below the range of human hearing – but it can be heard by other fin whales thousands of kilometres away. In the 1960s, when United States navy personnel first heard the whales’ deep moans, they could not believe they were animal sounds.

Migration

The fin whale is also remarkable for its long migration, and its speed. It travels as far as 20,000 kilometres each year from the Antarctic to the tropics to mate and calve. Known as the ‘greyhound of the oceans’, it is noted for its stamina. One whale averaged 17 kilometres per hour over 3,700 kilometres.

Population

The southern hemisphere population is estimated to be about 20,000, a fraction of the pre-whaling numbers. From the 1950s to the 1970s Soviet whalers killed 720,000 in the Southern Ocean region.

Southern Right Whales

Distribution

The southern right whale is the baleen whale most closely associated with New Zealand because it used to come inshore to sheltered harbours to mate and calve. Other species of baleen whales were usually seen further out to sea as they migrated between their Antarctic feeding grounds and breeding grounds in warmer latitudes.

Southern right whales used to occur as far north as the Kermadec Islands, along New Zealand’s coasts, and as far south as the subantarctic Auckland Islands and Campbell Island. Today they are rarely sighted around the mainland.

Appearance

The right whale is a large, stocky, black whale, 15–18 metres long with broad flippers. Its lack of a dorsal fin makes it easy to identify. The arched upper jaw is covered in callosities – crusty outgrowths of skin which are often made white by infestations of whale lice. It also has a unique blow, with the water rising in two columns to form a ‘V’ 5 metres high.

Population

Before whaling there were estimated to be 10,000 in the whole New Zealand region. In the 2000s there were probably about 250 (mostly around the Auckland and Campbell islands). But around New Zealand’s mainland the few sightings made since the late 1990s suggest that there are fewer than 30 right whales in the population. The low numbers persist despite protection since 1935, perhaps because females only calve every three years.

Humpback Whale

The humpback’s scientific name is Megaptera novaeangliae. Megaptera means ‘big wing’. This refers to its flippers, the largest appendages of any animal – up to 5 metres long and about a third of its length. The name ‘humpback’ came from whalers who noticed that, just before diving, this whale arched its back more than others, exaggerating the hump around its dorsal fin.

Appearance

Humpbacks are black with variable white markings on the underside of the tail fluke. These markings, like flaking white paint, are unique to each whale. The large flippers are usually white. The head is knobbly with protuberances, and the whale’s jaw and throat grooves are often encrusted with barnacles.

Migration

Humpbacks are occasionally seen off the New Zealand coast, swimming between the Antarctic, where they spend the summer feeding on krill, and the tropics, especially Tonga, where they breed in winter. They often used to travel north along the east coast of New Zealand and back southwards down the west coast, sometimes passing through Cook Strait.

Population

Since the end of humpback whaling the numbers have only slowly increased, despite big increases in Australian waters. However in 2004, 35 were seen in a two-week period in Cook Strait.

Sei Whale

Capable of outrunning sail and rowboats, the sei whale was protected from whaling by its remarkable speed – until the advent of motorised chasers. The sei has been recorded at 50 kilometres per hour in a sprint. One travelled 4,320 kilometres in 10 days, indicating an average speed of 16 kilometres per hour if it made the trip without a rest.

Appearance

Medium sized for a baleen whale, at an average weight of 20–25 tonnes and a length of 15–18 metres, the sei is nevertheless the equivalent of four large elephants. It is lean and sleek, steely grey, and has a high dorsal fin. It is estimated to live for more than 50 years.

Feeding

Sei whales use two feeding methods. With their mouths half open they skim the sea’s surface for prey, then swallow what has collected on their 300–400 baleen plates. Alternatively, they open their mouths wide, taking in a huge quantity of food and water, then expel the water to leave the food behind.

Migration

Around February and March sei whales migrate south to Antarctic feeding grounds, but do not venture near the pack ice, as blue or fin whales do. They return to warmer waters to calve, passing through the Pacific Ocean to the east of New Zealand between the mainland and the Chatham Islands. The International Whaling Commission, which monitors whale populations, has no estimate for sei whale numbers.

Bryde’s Whale

Sometimes described as the ‘tropical’ whale, Bryde’s whales prefer waters warmer than 20°C, which are generally found in northern New Zealand.

It is the most common of the baleen whales around the New Zealand coast, and is seen mainly in springtime in the Bay of Plenty, Hauraki Gulf and off the east coast of Northland. Whether it migrates long distances is uncertain. Some experts believe Bryde’s whales, seen off the coast, mate and calve locally.

Appearance and diet

From a distance the Bryde’s whale is often confused with the sei: they are both sleek and grey, with a pointed dorsal fin. The Bryde’s is the second smallest of New Zealand’s baleen whales (the minke being the smallest), with an average weight between 16 and 20 tonnes and a length of 12–15 metres. Unlike many other baleen whales, which eat krill in polar waters, the Bryde’s feeds on fish, such as pilchards, mackerel and mullet.

Whaling

The Bryde’s has been spared large-scale whaling. Up until 1962, New Zealand whalers working at the Whangaparapara station on Great Barrier Island hunted Bryde’s whales, although only 17 were ever taken. Out of an estimated original population of 60,000, there may be 40,000 left.

Minke Whale

The minke whale is now believed to consist of two species:

- The common or northern minke whale, which in its large form is confined to the northern hemisphere. However, a sub-species, the dwarf minke, is found in New Zealand.

- The Antarctic or southern minke whale, which is confined to the southern hemisphere including New Zealand.

In New Zealand minke whales are not commonly seen, although of all the baleen whales they are the most likely to become stranded on the coast.

Appearance and diet

The dwarf minke, which is most often seen, is about 7 metres long, while the southern is about 9 metres long. The minke is also called the ‘piked whale’ or ‘sharp-headed finner’, because of its sharply pointed head. It is chunkier than its relatives and has a dark grey back with variable whitish markings. Sometimes there is a distinctive white band on the flipper.

Like the blue whale, the minke favours cold waters close to the Antarctic ice where it feeds on krill, but around New Zealand it relies more on fish and squid.

Whaling

Whalers did not bother with minkes until the latter half of the 20th century, when the larger whale species had been hunted out. Since 1987 the Japanese have been killing more than 300 minkes a year, in defiance of world opinion, for purposes they define as scientific research.

There is debate about the size of the world’s minke population, but it is likely to be between 500,000 and 1,000,000.

Sperm Whale

The sperm whale was named by the early whalers who discovered whitish oil in the whale’s head and thought the fluid looked like semen. It is possible that this spermaceti oil helps to focus the sound emitted during echolocation, and to stun the whale’s prey.

The sperm whale is by far the largest of the toothed whales, and the size difference between males and females is much more marked than in any other whale species. Males are about 18 metres long and weigh 32–45 tonnes, and are up to 40% longer and 300% heavier than females. The sperm whale’s brain weighs almost 10 kilograms, and is the heaviest of any animal.

Appearance

The sperm whale has a huge square head, with a small underslung jaw. Its skin is dark grey to dark brown and corrugated. In place of a dorsal fin, it has a hump and a series of knuckles. It has triangular flukes which it raises before diving. The blowhole is off to the left and when the whale blows, the blast shoots forward at a 45º angle.

Distribution

Sperm whales are found at Kaikōura in the South Island, to the west of Stewart Island, off East Cape and North Cape, and in pockets to the west of New Zealand. In the 19th century the major hunting grounds were north-east of New Zealand near the Kermadec Islands.

Feeding

The sperm whale captures its prey by diving deep into the ocean’s trenches. It reaches depths of 3,000 metres, descending at a rate of over 100 metres a minute. The whale can stay there up to an hour and, in the dark, find its prey by echolocation. On surfacing, the whale takes 45–50 breaths to re-oxygenate.

Social groups

The social behaviour of sperm whales is unusual. Females and males live mostly separate lives. Small groups of up to 50 closely related whales, usually consisting of several females and immature whales of both sexes, live together for up to 10 years. Their need for co-operation is vital: when a cow spends an hour away on a deep fishing expedition, her vulnerable calf requires babysitting. Young males leave the whale nursery school at between 7 and 10 years of age to form bachelor schools before starting to breed at about 25. As adults, the males become increasingly solitary and begin to feed in Antarctic waters.

Sperm whales at Kaikōura

Kaikōura, on the east coast of the South Island, is the only place in the world with a deep-water canyon close to shore that attracts sperm whales. Just 4.5 kilometres from shore, the continental shelf suddenly falls away and the ocean plunges 1,000 metres. Here the whales dive for the famed giant squid, as well as groper and ling.

Kaikōura is a foraging ground for about 80 bachelor whales. About half of those that have been identified remain at Kaikōura for more than one season. The others move on. These are probably older males, passing through on their way to Antarctic waters, or expelled by the younger whales.

While Kaikōura sperm whales eat squid, fish also make up a significant proportion of their diet. Studies in the 1960s of sperm whales killed in the Cook Strait region showed that squid accounted for 65% of their food, and groper and ling the remaining 35%. Depending on their size, sperm whales eat anywhere between 400 and 1,000 kilograms of food a day, or 3% of their body weight.

Pygmy sperm whale

The pygmy sperm is a small grey whale up to 4 metres long, which is more often seen after stranding than at sea. It too has spermaceti oil in its head. The pygmy is hard to distinguish from the very much rarer dwarf sperm whale .

Document Actions

Like us on Facebook

Like us on Facebook